The Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution protects people from random and arbitrary stops and searches. Although the federal government claims the power to conduct certain kinds of warrantless stops within 100 miles of the U.S. border, important Fourth Amendment protections still apply. This helps you understand your rights within the 100-mile border zone.

Share this issue: Select a scenario Related Know Your Rights Select a scenario

U.S. Customs and Border Protection, the federal agency tasked with patrolling the U.S. border and areas that function like a border, claims a territorial reach much larger than you might imagine. A federal law says that, without a warrant, CBP can board vehicles and vessels and search for people without immigration documentation “within a reasonable distance from any external boundary of the United States.” These “external boundaries” include international land borders but also the entire U.S. coastline.

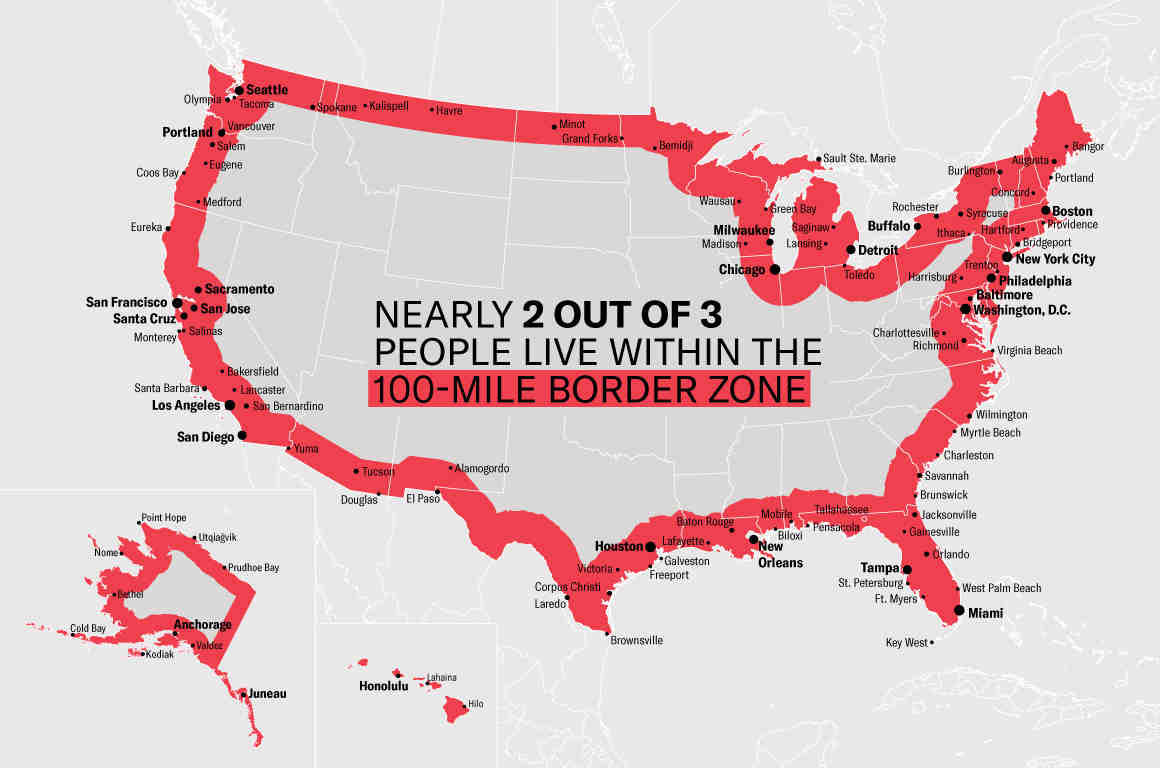

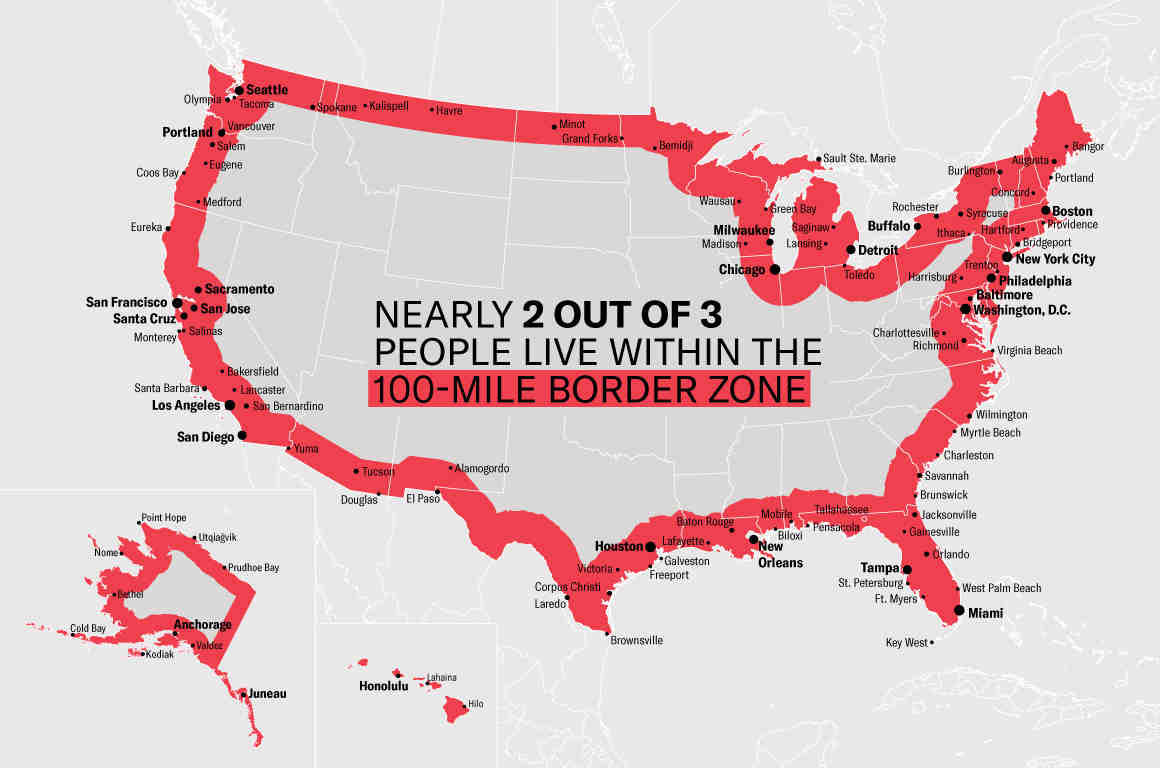

The federal government defines a “reasonable distance” as 100 air miles from any external boundary of the U.S. So, combining this federal regulation and the federal law regarding warrantless vehicle searches, CBP claims authority to board a bus or train without a warrant anywhere within this 100-mile zone. Two-thirds of the U.S. population, or about 200 million people, reside within this expanded border region, according to the 2010 census. Most of the 10 largest cities in the U.S., such as New York City, Los Angeles, and Chicago, fall in this region. Some states, like Florida, lie entirely within this border band so their entire populations are impacted.

Share this scenario:The Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution protects against arbitrary searches and seizures of people and their property, even in this expanded border area. Furthermore, as a general matter, these agents’ jurisdiction extends only to immigration violations and federal crimes. And, depending on where you are in this area and how long an agent detains you, agents must have varying levels of suspicion to hold you.

We will examine specific scenarios where one might encounter CBP in more depth, but here are your key rights. These apply to every situation, outside of customs and ports of entry.

Other important factors to keep in mind:

As part of its immigration enforcement efforts, CBP boards buses and trains in the 100-mile border region either at the station or while the bus is on its journey. More than one officer usually boards the bus, and they will ask passengers questions about their immigration status, ask passengers to show them immigration documents, or both. These questions should be brief and related to verifying one’s lawful presence in the U.S. Although these situations are scary, and it may seem that CBP agents are giving you an order when they ask you questions, you are not required to answer and can simply say you do not wish to do so. As always, you have the right to remain silent.

Refusing to answer CBP’s questions may result in the agent persisting with questioning. If this occurs, you should ask if you are being detained. Another way to ask this is to say, “am I free to leave?” If the agent wishes to actually detain you — in other words, you are not free to leave — the agent needs at least reasonable suspicion that you committed an immigration violation to do so. Also, if an agent begins to question you about non-immigration matters, say to ask about drug smuggling, or if they haul you off the bus, they need at least reasonable suspicion that you committed an offense in order to briefly detain you while they investigate. You can ask an agent for their basis for detaining you, and they should tell you.

The longer CBP detains you the more suspicion they need — eventually they will need probable cause once the detention goes from brief to prolonged. If the agent arrests you or searches the interior of your belongings, they need probable cause that you committed an offense. You can ask the agent to tell you their basis for probable cause, and they should be able to articulate their suspicion.

Share this scenario:CBP operates immigration checkpoints along the interior of the United States at both major roads — permanent checkpoints — and secondary roads — “tactical checkpoints”— as part of its enforcement strategy. Depending on the checkpoint, there may be cameras installed throughout and leading up to the checkpoint and drug-sniffing dogs stationed with the agents. At these checkpoints, every motorist is stopped and asked about their immigration status. Agents do not need any suspicion to stop you and ask you questions at a lawful checkpoint, but their questions should be brief and related to verifying immigration status. They can also visually inspect your vehicle. Some motorists will be sent to secondary inspection areas at the checkpoint for further questioning. This should be done only to ask limited and routine questions about immigration status that cannot be asked of every motorist in heavy traffic. If you find yourself at an immigration checkpoint while you are driving, never flee from it — it’s a felony.

As before, when you are at a checkpoint, you can remain silent, inform the agent that you decline to answer their questions or tell the agent you will only answer questions in the presence of an attorney. Refusing to answer the agent’s question will likely result in being further detained for questioning, being referred to secondary inspection, or both. If an agent extends the stop to ask questions unrelated to immigration enforcement or extends the stop for a prolonged period to ask about immigration status, the agent needs at least reasonable suspicion that you committed an immigration offense or violated federal law for their actions to be lawful. If you are held at the checkpoint for more than brief questioning, you can ask the agent if you are free to leave. If they say no, they need reasonable suspicion to continue holding you. You can ask an agent for their basis for reasonable suspicion, and they should tell you. If an agent arrests you, detains you for a protracted period or searches your belongings or the spaces of your vehicle that are not in plain view of the officer, the agent needs probable cause that you committed an immigration offense or that you violated federal law. You can ask the agent to tell you their basis for probable cause. They should inform you.

Share this scenario:CBP conducts yet another interior enforcement activity: roving patrols. During these patrols, CBP drives around the interior of the U.S. pulling motorists over. For these operations, the Supreme Court requires CBP to have reasonable suspicion that the driver or passengers in the car they pulled over committed an immigration violation or a federal crime. If they do pull you over, an agent’s questions should be limited to the suspicion they had for pulling you over and the agents should not prolong the stop for questioning unrelated to the purpose of the stop. Any arrest or prolonged stop requires probable cause. You may ask the agent their basis for probable cause, and they should tell you. In this situation, both the driver and any passengers have the right to remain silent and not answer questions about their immigration status.